Adam Taggart, CEO & Founder of Wealthion

The official unemployment rate: an imperfect view

By some measures, the labor markets were a bright spot in an otherwise dreadful 2022 economy. Year-over-year, payroll employment rose by over six million jobs, while the official unemployment rate declined, touching below 3.9%. These numbers would probably represent strong economic growth in a normal macro environment; however, the post-pandemic economy isn’t normal, and the unemployment rate has become a poor economic indicator on its own. To analyze the impact that current and future unemployment will have on our economy, we need to dig deeper into what employment means today, and where the official measurements are falling short.

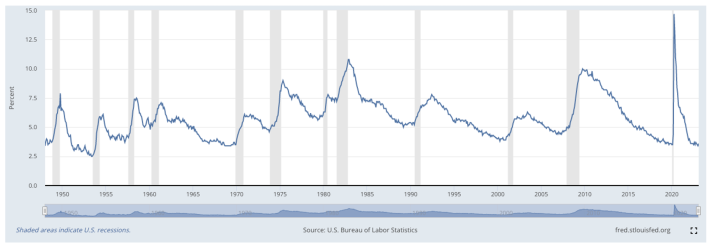

U.S. Unemployment Rate Per the Bureau of Labor Statistics

The reality is that our current employment situation is probably worse than the consensus view, and as a lagging indicator, the unemployment situation is bound to get worse as the Fed delivers on its promise of demand destruction through its aggressive campaign of rate hikes to-date.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines “unemployed” as people who are jobless, available to work, and currently seeking a job. The number of Americans who currently fall in that category is about 5.9 million, a number that has been relatively steady over the last year. With an unemployment rate under 4%, the 5.9 million out of work certainly doesn’t look like an economic risk on its own. However, the number of people in their prime working years who are not employed and not seeking employment is added, we get a much more somber picture. That non-working demographic isn’t counted in the unemployment rate, and the number is growing.

About 100 million Americans are currently outside of the labor force, which means almost one in three American adults are not employed. While a portion of this population are retirees, students, military, caretakers, and otherwise occupied with vocations that don’t fall into the category of full-time employment, there is a growing demographic of people who can work, but are simply choosing not to. Some leading economists like Nicholas Eberstadt estimate that about seven million prime working age men are available to work, but decline to participate in the labor force.

Whatever the reason for this trend, it is not for a lack of job openings. There are currently 10 to 11 million unfilled positions. Open jobs have jumped by 4 million since the pandemic. Demographics suggest that we should have a labor surplus, and instead, we are looking at a labor shortage. It is an unprecedented economic paradox–an abundance of available jobs amid an excess capacity of potential human capital willfully abstaining from participating in work.

How did we get here?

The labor legacy of the Great Resignation

This unparalleled situation can, at least in part, be attributed to the stimulus injected into the economy by the U.S. government during the Covid-19 pandemic, stimulus that was intended to help avoid a greater economic disaster.

Unemployment spiked temporarily and severely during the early stages of the pandemic. Pressured by this unprecedented economic shock, policymakers overshot in their efforts to avoid another depression. The excess stimulus aided savings rates, which doubled in 2020/21. Any sizable government intervention brings unintended consequences, and the $2.5+ trillion in new stimulus substantially added to household wealth, as people working from home had little opportunity to spend excess cash.

Lower labor participation rates began before the pandemic, but those trends accelerated as the economy raced back from 2020’s recession, fueled by the higher savings accumulated through the massive government stimulus.

The spike in household wealth certainly tempted some people to retire early. It also allowed some people of prime working age to simply resign and not return to work at all. But the money that many have used as a substitute for job earnings is nowhere near sufficient for a lasting reprieve from the workforce. The excess money is going to run out. And when it does, many current non-participants in the labor force may then need to look for work, increasing demand for jobs.

But by then how many of today’s job’s will still be available? If the Fed has indeed achieved its mission of demand destruction, labor markets may already be far into layoff mode – disappointing the new wave of aspirants hoping to be hired back.

The Fed won’t stop until unemployment rises

The Fed and other policymakers paint a rosy picture of current unemployment, in some part due to the outdated way in which the government measures it. The effect of this is that the Fed has pointed to the low unemployment rate as justification for continuing to ramp up interest rate hikes without pausing to let the 450 basis points worth of previous hikes work through the economy and slow it down.

In fact, unemployment is effectively rising, but the Fed isn’t seeing it as it misinterprets lagging data that is suspect to begin with. Since May 2022, the U.S. economy has lost about 10,000 full-time jobs. The job growth over that period has instead been in part-time positions. This is a sign of a weakening economy, indicating that more people are required to take on multiple side-jobs to stay afloat. A closer look shows that total U.S. full-time workers declined by 10,000 over a period of 10 months. Meanwhile, part-time workers soared from 25.9 million to 27.4 million, an increase of 1.5 million (source: Zero Hedge).

The recent BLS Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and Payrolls data beats are largely due to big seasonal adjustments. Also, the data does not align with privately-reported and more real-time jobs data. For instance, the data provided by outplacement service Challenger, Grey & Christmas diverges significantly from Initial Jobs Claims data reported by the BLS, yet aligns closely with with the accelerating spike in layoffs seen this year.

All this messy, outdated data has been influencing the Fed to keep tightening, likely too much as we head into the recession the Fed is causing. Once the BLS unemployment rate starts rising, it may increase for a long time as the lag effects of the Fed’s excessive tightening slam into the economy for quarters to come. By then, it will be obvious to all that we have a problem with unemployment, and too late to stop its continued rise.

Plus: Here’s What Experts See Ahead

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.